When crisis hits, is the time for talk over?

The international Coronavirus outbreak has serious implications for democracy worldwide. In the #NeverLockdownDemocracy blog series, the NIMD network takes a global view of how we can respond to the pandemic as we continue our work to protect democracy. Follow @WeAreNIMD on Twitter and the hashtag #NeverLockdownDemocracy to never miss a post.

By Violet Benneker, Knowledge Advisor, NIMD

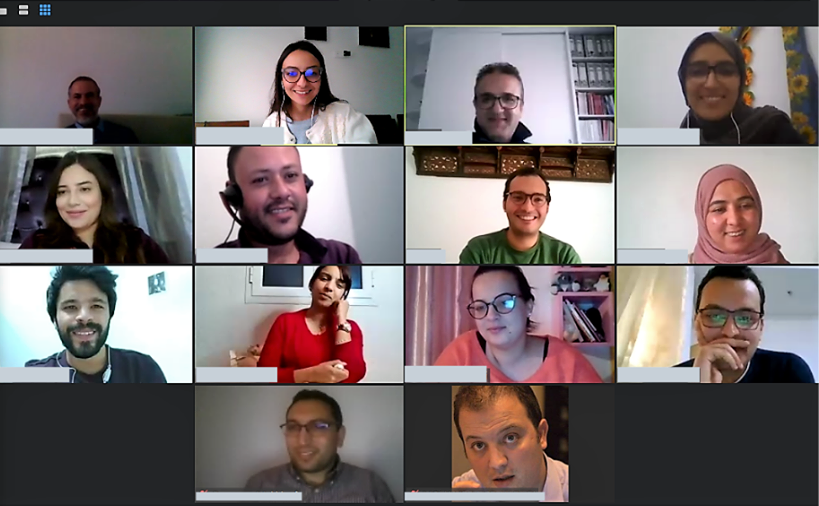

The COVID-19 crisis poses significant challenges to inclusive political dialogues, as physical meetings have become impossible in many places around the world. The way forward has taken NIMD’s inter-party dialogue platforms online for the first time in NIMD history.

This is not without its obstacles. Dialogue relies on positive personal interaction and trust between individuals. Unfortunately, our brains are not wired to do this online.

Yet NIMD’s current experience shows that the COVID-19 crisis also presents unique opportunities. We can still work to limit the damage to inclusive politics we see happening around the world, and support political parties to pick up the democratic pieces of this crisis through dialogue.

The challenge of an online dialogue

We place building trust at the heart of NIMD’s approach to dialogue. This is why we create safe spaces to house our inter-party dialogue platforms. With safe spaces, I mean spaces that are, among other things, shaped by jointly created and equally applied rules of engagement. Such rules make sure all participants of a dialogue can speak and be heard on equal terms. This allows political parties to begin establishing new relations of trust and enables inclusive decision-making processes – even in the most fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Almost by definition, a safe space for dialogue seems to imply a physical space and inter-personal contact. The participants need to hear each other clearly, see each other fully, read each other’s body language. However, this is difficult to replicate online.

“Can you hear me?”

Indeed, it is difficult to overstate the importance of this inter-personal contact. A dialogue that deals with sensitive political issues is not just about sending information, which happens easily in online meetings. Successful dialogue platforms also rely on specific skills such as active listening, reading body language, and creating a willingness to share each other’s true needs and interests. Without that level of engagement, dialogues can quickly fall apart, with the worst-case scenario of parties returning to conflict.

After weeks of lockdown, few would deny that this type of real listening is very hard to do online. How many times have you struggled to really understand what that one colleague was saying due to connection problems (“can you hear me?”), experienced the difficulty of bringing a point across through a screen (“sorry, I missed that last bit”), or been distracted by something in the house? This is no different for the politicians that we work with.

The way forward for inter-party dialogue

Our teams across the world now find themselves at the forefront of coming up with creative solutions and practical fixes. They are focusing all their energy on making sure governments’ handling of the COVID-19 crisis is supported by political dialogues that are inclusive and responsive to citizens’ needs.

- Social etiquette for online political dialogue

Our first challenge is to recreate NIMD’s offline safe spaces in an online environment. Crucially, this means that we have to reinvent the rules of our inter-party dialogues if we are to meet the opportunities, and confines, of doing dialogue digitally.

In Tunisia, NIMD’s partner Centre des Etudes Méditerranéennes et Internationales (CEMI) was one of the first dialogue platforms to go completely online. They are tackling how to recreate the essential preconditions to dialogue in an online platform. The facilitators have found they have a crucial role in supporting the confidence of politicians to engage with each other online, and need to be much more involved than in the normal, offline setting.

Together with the political parties, they are now creating new rules and social norms for online dialogue. These include online social etiquette in areas such as time keeping, speaking and listening. In this way, they are safeguarding some of the most important principles of dialogue, and are recreating a safe space online where everyone can speak, listen, and is heard.

- Broadening the online audience

Doing dialogue digitally is a challenge, but at the same time, the open nature of online environments is giving us exciting new opportunities to work for inclusivity.

Take the example of Myanmar, where the COVID-19 crisis has come on top of the intensifying ongoing civil wars. Next to developing strategies to create secure and safe spaces for online political dialogue in such a difficult context, NIMD’s partner MySoP is taking the opportunity to engage with a wider audience than usual. For example, they will be facilitating an online meeting with over 100 high level representatives of political parties to talk about the crisis and the impact it has at the regional level. In this way, MySoP continues to contribute to accountable and inclusive political decision-making, even in times of crisis.

- Acting as citizens’ offline voice

In some countries, we are faced by challenges that are beyond our control and make the move to a (temporary) online programme impossible. For example, there is no equal access to the internet, or connections are not stable enough for lengthy online meetings. In addition, some governments readily use the excuse of the current crisis to postpone political dialogue and rule by decree.

In such countries, NIMD’s dialogue platforms have taken up offline opportunities to act as an avenue for wider society to reach decision-makers with their needs and demands, and feed them with alternatives. One example is Uganda, where NIMD facilitates the interparty-dialogue platform IPOD. There, the main challenges include large differences in access to stable internet connections across the country. This is why NIMD in Uganda has taken up their goal of supporting inclusive politics in new, offline ways.

In response to COVID-19, Uganda created a national taskforce for the handling of the health crisis. Subsequently, NIMD Uganda proposed the IPOD members (all parties represented in parliament) to be included in the national taskforce in order to avoid dominance by the Executive and to promote inclusiveness of policy-making. This proposal has resulted in permits for Secretaries General and leaders of the political parties to continue their work, and bring citizens’ offline voices directly to the taskforce’s ears.

Preparing for the future

The effects of COVID-19 crisis on inclusive political dialogue are acute and grave, and it makes our work difficult. And yet, as governments around the world are ramping up repression and actively closing civic space, our work for inclusive political dialogue is more pressing than ever – even if it is also harder than ever.

This is why I continue to be impressed by all NIMD teams around the world, who are able to find solutions and practical fixes to support inclusive political dialogue – and inclusive democracies in the long run, long after the lockdowns are lifted.