US elections: Drawing lessons on inclusive democracy

What do the US elections mean for democracies around the world? How does the rhetoric surrounding the campaigns affect the way we see democracy as a global society? And what lessons can be learned from the mass mobilization of voters in our journey towards more inclusive democracies and societies around the world?

NIMD’s Director, Thijs Berman reflects on the repercussions of the US elections. He brings us insights from our programme countries, on what they are thinking about, and on how they feel the elections have started to have an effect beyond the US.

Four weeks ago, the US and the world waited on the edge of their seats as the ballots were counted. As the votes trickled in over the course of the week, I must admit to having developed a bit of an unhealthy obsession.

With all the focus on the effects of this election on the US, it occurred to me that this highly anticipated and intensely watched event would reverberate across the world. After all, the world’s eyes were on democracy at work in a country with deeply polarized visions on society, which even led to fears about the potential of a violent outcome.

I reached out to our colleagues in the NIMD network to find out how they feel about the impact of this election in their countries.

The way we talk about democracy and elections

The first thing that struck me was how many of my colleagues feel the rhetoric around the electoral campaign will impact the situation in their own country.

Words matter. The way we talk about democracy is crucial to the strength of democracy around the world – it shapes the importance we place on our democracies and the trust we as populations place in the democratic institutions that hold that democracy up.

My colleagues in Kenya express concern that Trump’s divisive approach towards the election and vote count could possibly fuel conflict, especially ahead of the 2022 general election in Kenya.

As Caroline Gaita, Director of our Kenyan partner Mzalendo, puts it: “Given our history with post-election violence, the US elections make us think. If leaders take on this kind of divisive route, how are Kenyans going to respond to it?”

Caroline feels that divisive rhetoric is not unique to the Trump campaign, however, and fears it could have long-lasting effects. In her view, Biden’s campaign was highly personalized. Depending on their race, gender or sexuality, Americans were targeted by the campaigns and made to understand what another term under Trump would mean for their welfare and rights.

For Caroline, this raises a mirror to Kenya’s history of personalized politics, where voting habits are traditionally tied to voters’ backgrounds. This is a history Kenya is currently trying to break out of, with more policy-based campaigns.

What this shows is the US’s diminished role as a moral authority and paragon of democracy. Rather than looking to the US model, Kenya will need to draw inspiration from its own progress, and continue to work towards a more inclusive democracy, especially with elections around the corner.

Inclusion and mobilization

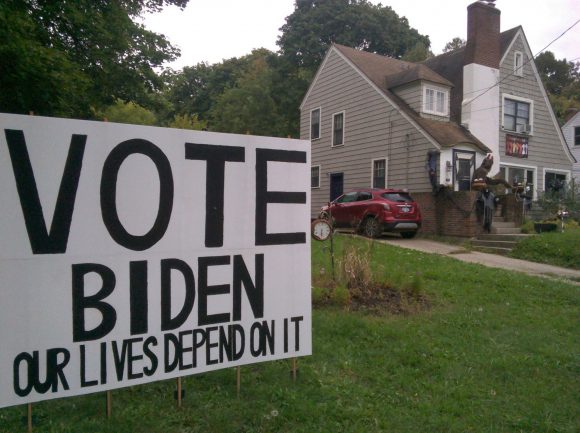

This presidential election was unprecedented in many ways. It may have breached almost every convention about respectful competition. But what was also unprecedented was the mobilization of voters on both sides – and perhaps this was partly due to the lack of respect. Never before have so many citizens put such tremendous efforts into encouraging people to register as voters. And never before have so many citizens cast their votes.

There was also an unprecedented increase in candidates from marginalized groups. The 2020 elections saw a 105% increase in the number of women running for Congress in comparison to 2016, including a 138% rise in women of colour. We also witnessed a 30% increase in the number of women running for State Legislature, and a 41% rise in LGBTQI+ candidates (more than the US has ever seen before).

At NIMD, we ask ourselves: How have political party processes facilitated the rise of women to the highest offices, for example? And how can we continue to empower politicians from minority groups, to see a similar increase in our programme countries?

We can also learn from the mass mobilization of US voters.

In Uganda, NIMD’s Country Representative Frank Rusa notes the high voter turnout and the razor thin electoral victories in some states that brought victory to Biden.

This just serves to show that every vote counts. It has inspired many political and civil society activists in Uganda to reflect on how to improve grassroot civic organization and mobilization, ahead of Uganda’s general election in January 2021.

Since the largest ever elections turnout in the history of America was in part due to young voters, these lessons could be especially pertinent in countries with a large youth population.

Young people are often marginalized from political processes, and our partners around the world can draw on the example of the US elections to ensure that this group exercises their civic rights, are informed and participate in political processes.

What will Biden’s presidency bring?

My colleagues’ responses to my enquiries about the elections show that the US elections themselves are already having an impact on democracies around the world.

But what will happen once Biden steps into the White House in January? Although some elements are clear, it’s still too early to know exactly what the Biden presidency’s foreign policy priorities will be. What really does stand out are the very different views across many of NIMD’s programme countries on what Biden’s term will bring.

In Central America, for example, our colleagues expect that changes in US foreign policy could have a significant positive impact.

In Guatemala, some sectors of the population are hopeful that Biden’s presidency will boost the fight against corruption. And there are hopes across El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras for a change in immigration policy, towards more humane treatment of immigrants to the US.

At the same time, conservative sectors in the region have been in favour of Donald Trump throughout his presidency and campaigns. Some, including the Pentecostal churches, may feel disenfranchised and resentful as US foreign policy turns away from some of the more traditional values within society.

Our colleagues from EECMD in Ukraine also observe differences in views in their country regarding the effects of the new Presidency, especially regarding stability.

Biden was at the forefront of an anti-corruption reform agenda as US Vice President. In Ukraine, some now hope that, with Biden bringing this back onto the agenda as a priority, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the rest of the country’s anti-corruption architecture will be reinforced. There are also hopes that Biden will help undermine an attempted counter-revolution that is currently gaining momentum in Kyiv with support from Ukraine’s pro-Russian political forces and the country’s oligarchs.

Others in this part of the world are more sceptical about the scope of the change. The Obama administration, many of whom will take on senior roles in Biden’s cabinet, failed to ease the Ukraine crisis back in 2015-16. The trust and hopes that some Ukrainians put in Biden to ease tensions, is not felt unanimously.

So, what’s next?

Time will tell how shifts in US foreign policy will affect our programme countries. For now, we will await 20 January having drawn lessons about inclusion and mobilization. Perhaps most importantly, the elections have shown a need to reflect on the power of language. As NIMD and as individuals, we have a responsibility to stand up for democracy, and to talk actively about its values. Because the repercussions of attacks on these values can tear at the fabric of society.

This is one of NIMD’s five strategic objectives, set out in our new Multi-Annual Strategy for 2021-25. We will talk actively about why democracy matters, underlining the importance of accountability, multiple parties, inclusiveness, dialogue and peaceful elections.

As our Multi-Annual Strategy outlines, we will back this up through our commitment to each of the democratic values above. In the next five years, we will strive to contribute to inclusive democracies, and amplify the voices of marginalized groups. We will continue to invest in dialogue, as a way to build trust, and foster peace and mutual acceptance through politics. And we will strengthen links between the population and political, so that politicians are accountable to the people they represent, and the people can feel more confidence in their democracy and democratic institutions.