#UN75: Trust me, I’m a politician.

In a world of dramatic changes and complex problems, from the COVID-19 pandemic to the climate crisis, we need collective action more than ever before.

That’s why, to celebrate its 75th anniversary, the UN has set up a global dialogue. At a pivotal moment in the UN’s history, they are asking people to make their voices heard; to put their heads together to define how we can recover better from the pandemic, and realize a better world.

NIMD couldn’t agree more with this special call for dialogue and inclusion, for opening up to discussion and hearing all voices. It is at the heart of what we do. And we believe it is at the heart of inclusive democracy.

Thijs Berman, Executive Director, NIMD

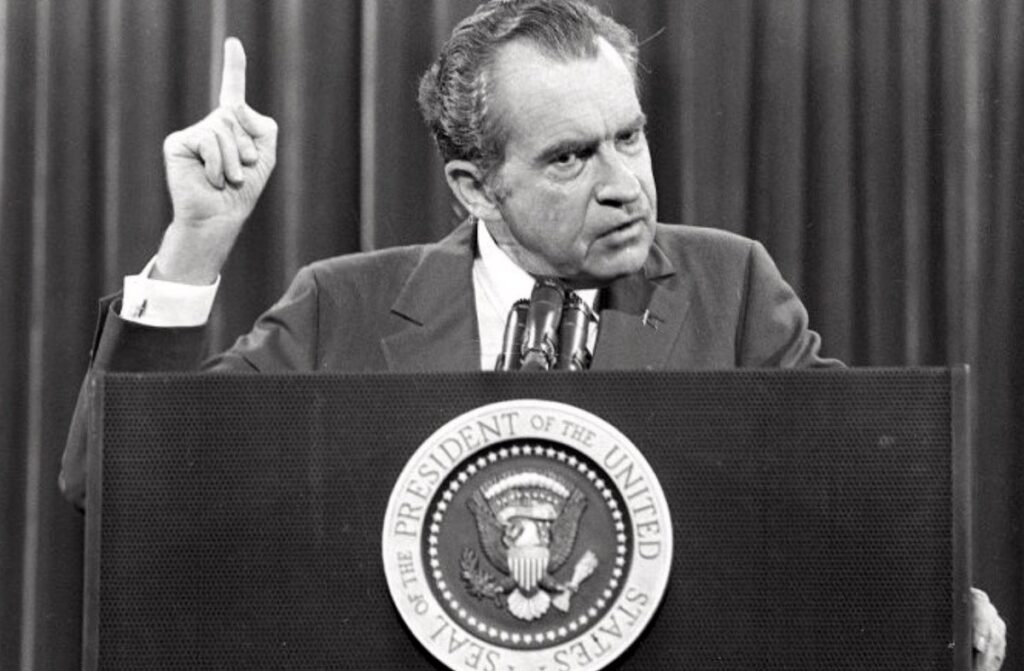

As a former politician, I am well aware of how many people view their elected leaders – with a degree of (sometimes justified) suspicion. I have been fortunate enough to witness from within how most politicians genuinely try to give the best they can. However, as a current voter, I can understand the distrust; how can I know for sure that the person I vote for will come good on their promises?

Frankly, one can’t always be sure. And there’s a chance you agree. Perhaps you’re a Machiavellian who believes politicians are all out for themselves. Maybe you actually think politicians can be trusted, but they are constrained by the confines of modern times thanks to Thomas Friedman’s ‘golden straitjacket’. Either way, it means electoral promises to the public come second to some greater motive, to unavoidable compromise – and so overly firm promises can’t be trusted.

But I want to see a change in our society – a change that means we can put a little more faith in our elected leaders.

The linchpin of any democracy

The evidence reflects a deficit of trust in politics worldwide. Take our friends in the UK – a dispiriting 2019 Ipsos MORI poll showed the public saw politicians as the profession least likely to tell the truth. Left or right, voters said we were less truthful than estate agents, advertising executives, and even bankers. The same apparent distrust is shown in other countries.

Unfortunately, this elusive trust is an essential ingredient for any democracy. If you’re going to continue a cycle of electing other people to protect your rights and interests, there needs to be trust in the cycle. If I vote for a specific party or candidate, I expect to see their policies implemented.

Is democracy keeping its promise?

The promise of democracy is that we work together, we build a government on consensus, and we advance as society together, leaving none behind. It’s the best way nations can govern themselves, and it’s what brought me into politics as a democracy advocate in the first place. But inequality persists, and we need to improve our democracies if they’re going to deliver.

In many countries, even advanced democracies like the Netherlands, we haven’t secured the public’s full-throated support for the whole political class. And indeed, a solid democracy relies on peoples’ ability to be skeptical, as well as their ability to trust. We aren’t looking for blind trust, but we need faith in the idea that politicians and political institutions are going to play by the rules and put the public first.

That is what permits voters to make fair and rational choices on election day, and to hold the political class to account.

However since the 1970s, the level of trust in politicians has fluctuated. Hardly an encouraging sign, but the lack of definite trend means we aren’t fated either way, and perhaps that trust is something that can be deliberately built, as opposed to being decided by fluke.

Oftentimes, the times when our trust is really tested is during a crisis. With COVID-19 and all its political fallout, I see a chance for us to put trust in politics on a decidedly positive trend.

The change I want to see

The change we need is dialogue being used as a tool to build up this trust. Not only now to commemorate the UN’s 75 years of service, but countries worldwide should be incorporating it into their democracies as a core aspect of their political culture.

NIMD’s most effective tool for building trust between politicians is its dialogue platforms. From our very first assignment in South Africa 20 years ago, we saw how deploying dialogue could totally change a political reality. From animosity to friends, and from enemies to partners.

So how will dialogue improve our trust in politicians and political institutions, and what should that dialogue look like? From our experience, we think it should be locally-led, designed for maximum inclusivity, and given the right support from third parties and experts to ensure all sides participate as equals. The public and politicians should be able to decide their agenda based on consultation, not some domineering national or international actor.

If we stick to those three principles as a starting point, then inclusive decision-making soon follows. This is our best opportunity to bring governance closer to the people, and thus get policies that are more aligned with public needs.

Trust at the heart of modern politics

When the UN announced the theme for its 75th birthday was dialogue, it gave me hope that the international community was realizing just how important building trust is for sustainable democratic development. And the fact that the UN has asked for its dialogue to be so far-reaching gives me hope that this isn’t just window dressing; it’s the real deal. Since NIMD’s work in South Africa over 20 years ago we have used dialogue as tool for progress in dozens of countries, and it works.

What’s more this is a continuous process. An ongoing conversation between governments and their people is what lies at the core of inclusive governance. Women and young people – to name but the most sizeable groups – have been shut out for too long, and dialogue is the right tool to, finally, bring them in from the cold.

So when you ask me what change I’d like to see, I answer by saying we must open dialogue between governors and the governed, the haves and the have-nots. Through dialogue, we as a global society can bridge the gap in trust, and start on a genuinely sustainable path to development.