Mali: Testimony of a crisis

This blog is by Mirjam Tjassing, NIMD’s country representative in Mali. Before joining NIMD, Mirjam worked as a diplomat for the Netherlands and published a book about the crisis in Mali, entitled Mali: Een Kaartenhuis (Mali: A House of Cards). Mirjam will be discussing her book and Malian politics at this year’s Afrikadag on 13 April in Amsterdam. Here she tells the story of what led her to write the book and share Mali’s political history.

In 2012 I moved from Burkina Faso to Mali to work as a political affairs officer at the Netherlands Embassy. Barely two weeks after my arrival, a rebellion broke out in the north, followed by a coup in Mali’s capital, Bamako. These were busy times for a political affairs officer; it was of the utmost importance to understand what was happening in Mali so we could determine what the Embassy could do to help stabilize the situation. In other words: I was thrown in at the deep end and I had to build up a large network quickly.

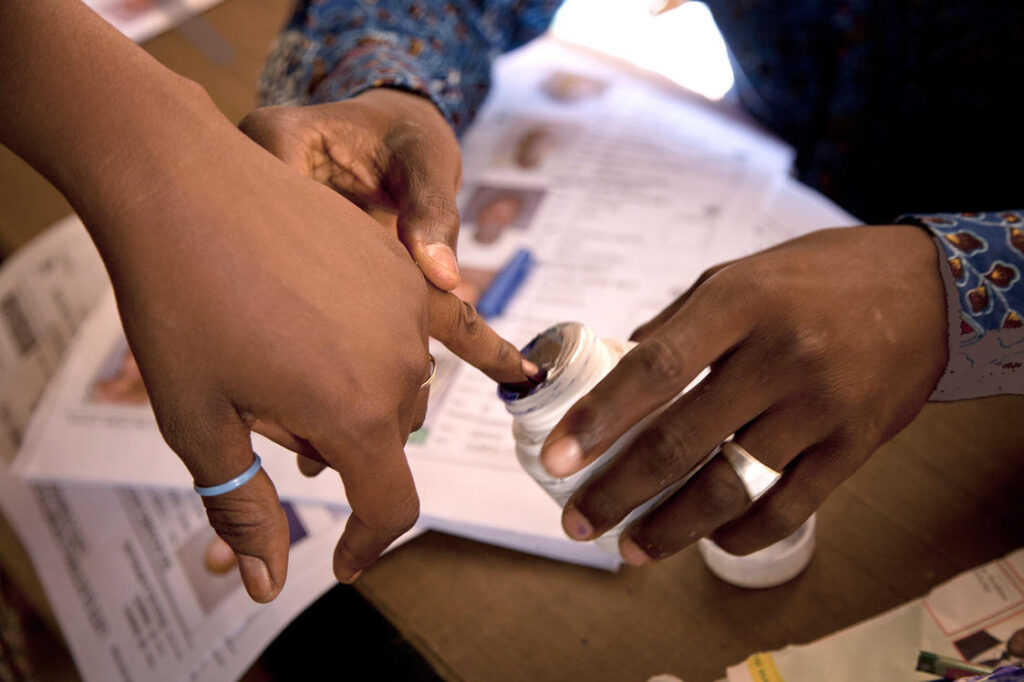

During the post-coup transition period, everyone tried to understand how things could have come this far. There was a large consensus that the culprits were corruption and nepotism, as well as the consensus politics of President Touré. These politics, which tried to give everyone a seat at the table of power and bought off opposition, had ultimately completely silenced public debate. During the transition period there was therefore much talk about thoroughly reforming the state. But who had the legitimacy to implement such reforms? Many felt the unelected government, which was strongly influenced by the military following the coup d’etat, was not. So the international community pressed for elections. But without reforms, the old system that had led to the rebellion and the coup was able to creep back in after the elections.

Once elections had taken place in 2013, all attention was focused on a solution to the ongoing crisis in the north. Tellingly, there was hardly any mention of state reform anymore. In the meantime, foreign diplomats succeeded each other at a rapid pace, because Mali had suddenly become a hardship posting from which people would move on after a short time. And so, the need for reform was wiped from the collective memory of the international community, and everyone fixed their attention on brokering a deal between the government and the armed groups. Again, there was hardly any room for the voice of the people. The message was clear: if you want to achieve something, democratic institutions don’t deliver much. You achieve more with weapons. This context allowed insecurity to spread to the centre of Mali.

Encouraged by a colleague from the embassy, I decided to write my book Mali, een Kaartenhuis. I wanted to highlight the need for Malian society to make the voice of its people heard and to reform its state institutions. And it was clear that the best way to do this was to tell this story mainly through the voices of Malians themselves. My book is not “the story of how it really works.” It is the story of what I have understood through years of conversations with Malian politicians, officials, researchers, students, traditional leaders, artists, activists, storytellers, drivers, and street vendors of Mali. And this is what I would like to share with you. Firstly because Mali is such a fantastic country, but also because Mali is closer to Europe than we think, and we are reliant on each other for a peaceful future.

Mirjam’s talk at Afrikadag takes place on 13 April at 11.30 in the ‘Marmeren Hal’ of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) in Amsterdam.