Lessons from Afghanistan

By Thijs Berman, Executive Director of NIMD. Thijs was Head of the European Union’s Election Observer Mission to Afghanistan in 2009 and 2014. He explores what went wrong in Afghanistan, and what advocates of democracy can learn for the future.

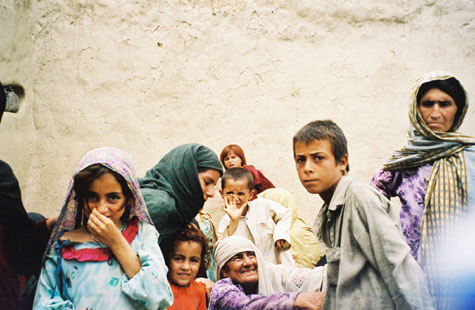

In twenty years, the drama of the Afghan people has seen three acts. The first act was marked by intense relief at the ousting of the Taliban regime and the hope for a better future, in particular for women and girls.

Many Afghans shared in this euphoria and optimism, putting their faith in the promises of democracy and freedom for all. They cast their votes in elections which they believed would herald this new era of freedom, courageously risking their lives to make sure their voices were heard in the new Afghanistan.

That faith and courage deserved to be respected by the international community and supported by transparent and long-term investment in democratic institutions, inclusive political dialogue led by the Afghan people, and zero tolerance for corruption and nepotism.

“Stability does not come from military might.”

But then came the second act, when these high hopes gave way to disillusion, cynicism and bitterness at broken promises. Accountable, transparent governance by an administration which came to power in legitimate and inclusive elections are the foundations of a true democratic society. Sadly, in Afghanistan, the legitimacy and credibility of the Afghan government were undermined by corruption and fraud, enabled by an international community which all too often turned a blind eye to the failings in the governments it helped create. The US-led coalition showed only half-hearted attempts to stem the growth of corruption, and failed to speak out against massive fraud in successive elections. This opened the way to the gradual erosion of the credibility and legitimacy of the Afghan administration.

Military missions, however big and expensive they may be, cannot solve societal questions. Stability does not come from military might. It comes from good governance and the growth of strong democratic institutions in an inclusive social fabric within the existing culture.

It’s not enough to plough money into a country without proper oversight, accountability, and investment in the democratic infrastructure. And it’s not as simple as putting in place elections and institutions. Democracy needs to come from within. It is embodied by a set of values – from accountability to collaboration and dialogue – shared by the people and those who represent them.

None of this happened in Afghanistan. Instead, the people who believed in these promises of a better future now hide behind locked doors, terrified of what the future will bring. These are the women who believed the promises of an equal and inclusive society and put themselves at considerable risk to enter politics; the young people who took up the mantle of human rights defenders; the journalists who trusted that they would work in a free and fair society.

And so Afghanistan enters its third act. The corrupt government has fallen, and the Taliban are back. It’s a third act of utter despair and chaos. The lessons from Afghanistan can be applied elsewhere, but they could also pave the way for another act in Afghanistan itself. There have already been protests in several cities. The younger generation clearly doesn’t give in so easily – people are not ready to abandon their freedoms after twenty years. They need the world’s support.