Elections in the time of COVID-19

The international Coronavirus outbreak has serious implications for democracy worldwide. In the #NeverLockdownDemocracy blog series, the NIMD network takes a global view of how we can respond to the pandemic as we continue our work to protect democracy. Follow @WeAreNIMD on Twitter and the hashtag #NeverLockdownDemocracy to never miss a post.

By Shaun Mackay, External Advisor, NIMD

As an organization, NIMD is fortunate. Despite the disarray caused by the pandemic, we have been able to provide some continuity to the parties, politicians and institutions we work with. For example our events and analysis continue via the internet, and NIMD’s dialogue platforms and Democracy Schools persevere with their vital work by using online services.

But what about when something much larger, such as a general election, falls in the times of pandemic?

The historical precedent

Any decision to postpone or cancel elections should not be made lightly; where circumstances permit, elections should always be held, and held on time. After all, even during the height of the Spanish flu which killed hundreds of thousands of Americans, elections were held in the US.

But this isn’t 1918, and the choices are not that simple.

The choices

Regular elections are fundamental to the proper functioning of a modern representative democracy. After four or five long years, the electorate gets to exercise what may be its only chance to speak on the performance of its public representatives – by either sanctioning them or renewing their mandates. But what is to be done when a runaway pandemic such as COVID-19 strikes in an election year?

This presents governments with an unenviable conundrum: how to protect the health of the democracy while protecting the health of the people. Is this even possible; or must a stark choice be made?

Some challenges for holding elections

So, what are some of the salient challenges that may confront states wishing to proceed with elections?

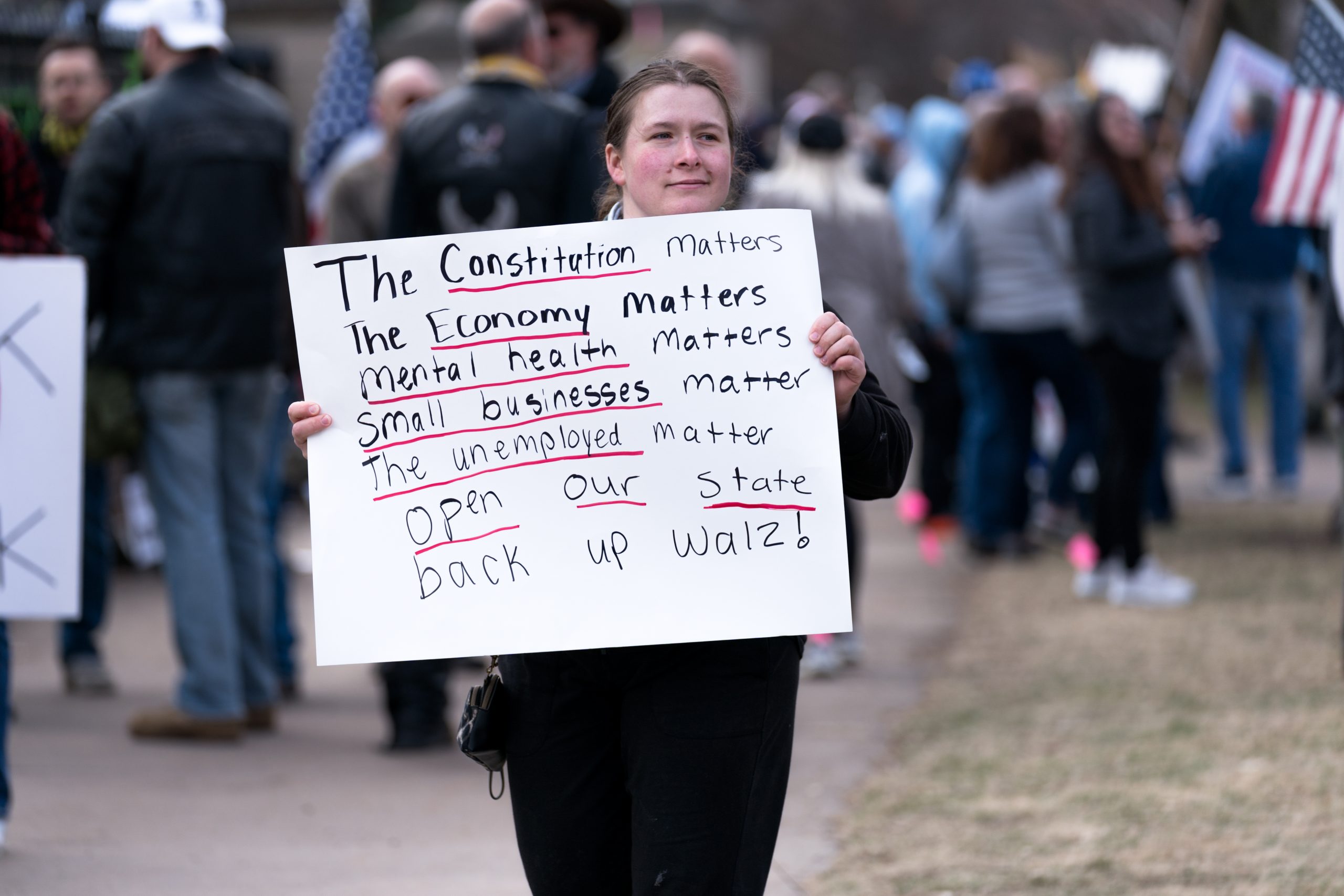

- Campaigning: the large rallies that typically mark elections will only be possible at the risk of exponentially spreading the virus. Virtual campaigning through social and print media (for those with access), and radio will have to suffice. This will raise the cost of campaigning, exclude the poor and indigent, further favouring those with access to finance and technology;

- Door-to-door canvassing: similarly, this may be dangerous and irresponsible depending on a country’s rate of infection. The high incidence of COVID-19 infections among politicians in Iran is speculated to have resulted from contact with constituents during their recent elections;

- Polling stations: these will be impacted as it becomes increasingly more difficult to find workers to man them. In the 2020 Wisconsin Democratic primary, an acute shortage of poll workers meant the city of Milwaukee was only able to provide five instead of its usual 180 polling stations. The upshot was unusually long lines that compounded the associated risks. Imagine this in a country that is unable to provide the same quantity and quality of protective gear and sanitizer; and

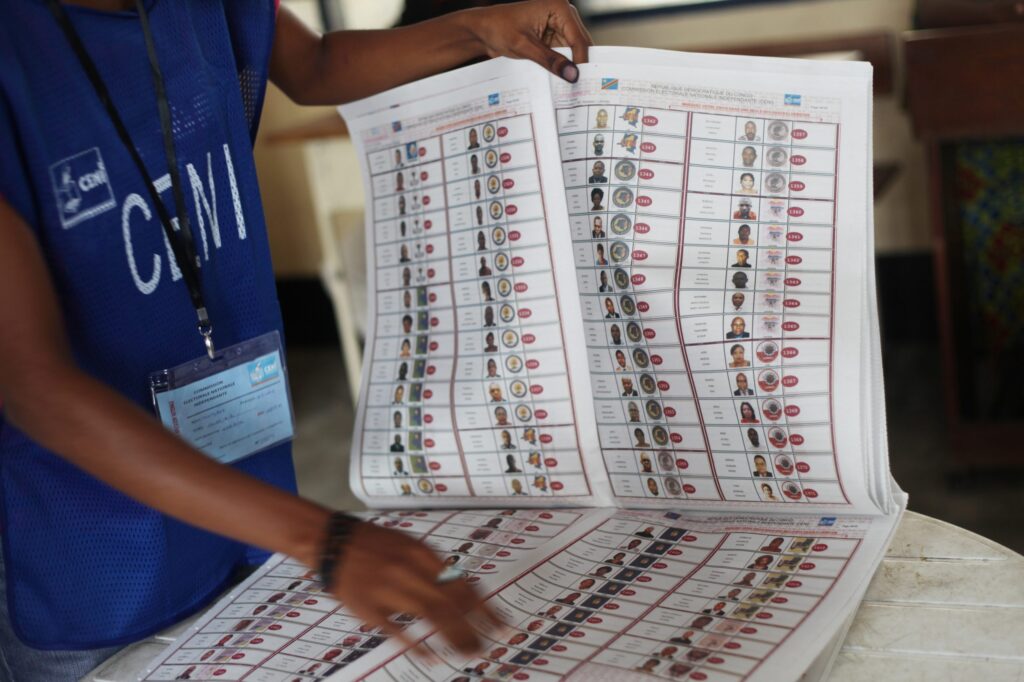

- Preparedness of electoral management bodies (EMBs): preparing for elections will be infinitely more difficult where movement and contact is constrained. Even more importantly, most EMBs are unlikely to be prepared for the increased administrative and logistical work necessary to hold elections during COVID-19, without risking the health of voters or diminishing their right to vote.

The show must go on!

A few countries have already taken the plunge and held elections. Mali, South Korea and the US (Wisconsin) are among them.

But here’s the rub. In some instances, these elections that have been held under the shadow of the pandemic have no doubt diminished the fundamental right of citizens to vote.

In Mali, COVID-19 added to a litany of other challenges, including terrorism and a protracted period without elections. The upshot was that these collective fears negatively impacted the rights of Malians to exercise their vote, as the vast majority opted to stay home.

Just 36% of registered voters turned out. This was disenfranchisement of the majority of voters.

And what about more ‘developed’ economies?

In the same vein, the Wisconsin elections, held after the courts overturned a decision by the governor to postpone elections, saw a significant decrease in voter numbers. Perhaps more importantly, it resulted in a record number of people who voted absentee – that’s postal, internet and proxy voting – which accounted for an estimated 80% compared to just 10% in 2016. People stayed home. A working postal service and access to technology, like the internet, are prerequisites for this. In many countries the limited connectivity levels alone will disenfranchise those unwilling to risk their lives by voting physically.

When South Korea commenced its early balloting protective gear, social distancing and sanitizers were visible throughout the polling stations. How many countries in the Global South can afford to roll out an election like this?

Cancelling elections: the dangers

With so many risks arising from running elections, it’s easy to suggest they ought to be called off until we’re at the other side of the Corona tunnel. Yet this response also carries risks of its own, both to the public and leadership:

- Mandate: legislators overshoot their electoral terms, thus leaving the government open to accusations of illegitimacy.

- Democratic rights: The states of emergency that have been invoked by several governments around the world, could well provide a pretext for those in danger of losing power to continuously cancel or postpone elections. As a consequence, the democracy will deteriorate. A case in point is Hungary, which recently passed a law giving power to Viktor Orban to rule by decree for an unlimited period of time.

- Precedent: it sets a dangerous precedent for democracies, especially where governments may seek to cling to power.

The solution? Put democracy at the heart of the decision

There is no one-size fits all solution here. This pandemic has disrupted our normal way of doing things – it will impact our democracies. But we must seek to limit this impact.

Each country will have to weight its own circumstance and ability to hold an election while safeguarding the health and ballot of its voters. Both are important and postponement is a responsible alternative for many countries that are unable to emulate the elections in South Korea. As was the case in Ethiopia, seeking consensus on this with the opposition parties will ensure wider political buy-in. And elections must be held as soon as the pandemic is under control.

Cancelling elections altogether is an anathema to democracy and should never be done. That’s why NIMD’s programmes have endeavoured to continue, despite the restrictions the pandemic brings. We cannot afford to allow our hard-won right to vote, to succumb to this pandemic as well!