El Salvador: ‘We need this broken moment to think about democracy’

El Salvador has been experiencing a democratic decline following the election of Nayib Bukele as President in 2019. While his promises to tackle crime and corruption proved popular with many, his methods have raised concern.

Bukele brought troops into Congress when lawmakers debated his proposals, replaced the constitutional chamber and the independent attorney general, and recently proposed a law imposing limitations on foreign funding for NGOs.

Here, Juan Meléndez, Executive Director of NIMD El Salvador, reflects on the conditions in El Salvador that allowed Bukele to seize the narrative and come to power, and looks ahead to how the country can return to the path of democracy.

When we look at the challenges facing El Salvador today, it can be tempting to place them in a global context. Nayib Bukele’s embrace of social media, the outsider narrative, and the confrontations with the elite are indeed familiar from other populist leaders around the world.

But there is also something uniquely Salvadorian about the rise to power of Bukele and the perilous position of democracy in the country today.

El Salvador has a long history of revolution and rebellion. Everybody has a bit of Che Guevara in them. During the 1960s and 1970s, there was an intractable battle between the forces of the left and right. A peace accord signed in 1992 ended our long civil war, but this Cold War mentality remained.

Sadly, this has cast a shadow over our democracy. The two parties that have dominated politics in El Salvador for the last three decades emerged from the different sides in the civil war – FMLN on the left and ARENA on the right – and they continued to oppose one another with no thought of working together. These parties always seemed to be in a state of deadlock. They would constantly block each other’s proposals in parliament, and the people just saw fighting and grew tired and disillusioned.

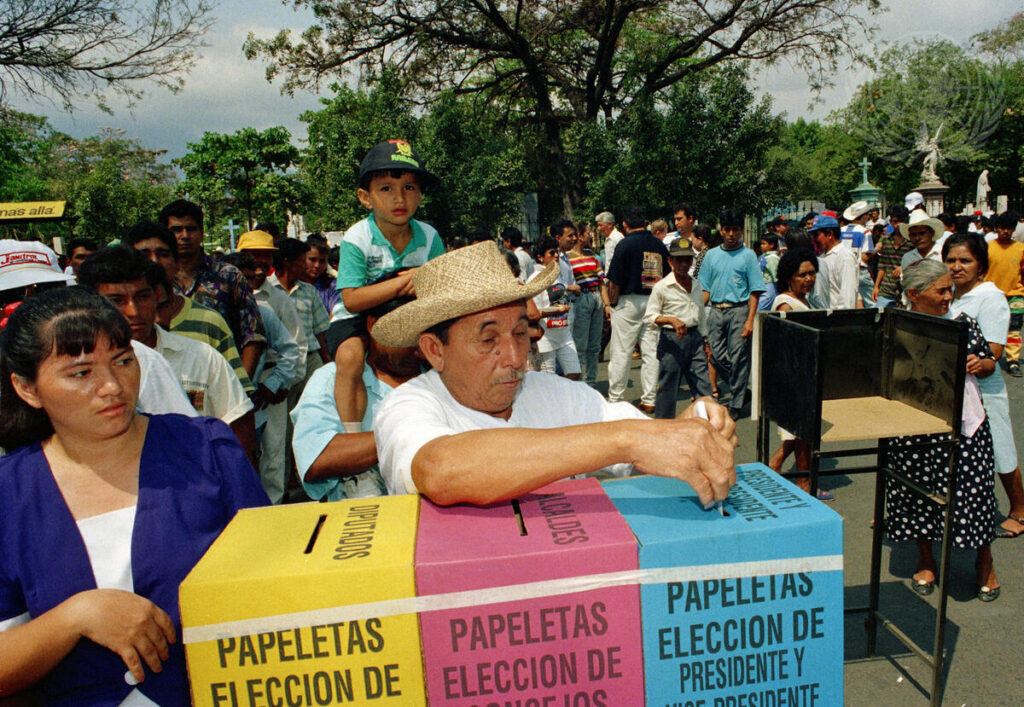

While the peace accord did lay down the conditions for democracy – a free press, free elections, and a multiparty system – nobody worked on the underlying democratic culture. No one talked about checks and balances. The multiparty, plural thoughts remained outside the box. The democratic system remained under construction.

In the meantime, nothing else changed. Everyone welcomed peace, but hopes that democracy would bring a better quality of life were never realized. Poverty and inequality remained. Many people left for the United States to find opportunities to earn money.

“People no longer believed in the government, they did not believe in democracy, they did not believe in politicians.”

Corruption is also a huge problem, with every political party implicated in graft cases. Of the last three presidents before Bukele, Antonio Saca is in jail and Mauricio Funes and Salvador Sánchez Cerén are in Nicaragua to escape corruption charges against them.

Given this history and context, it is not surprising that people lost their faith. They no longer believed in the government, they did not believe in democracy, they did not believe in politicians. So when Bukele positioned himself as an outsider, against the elites and a bit of a rebel, this was an appealing narrative.

But while I am dismayed about the threats to an independent judiciary in El Salvador and increasing pressure on opposition forces, I am also hopeful.

The election of Bukele has given us an opportunity. In the past, people did not think that talking about democracy was necessary. There was an assumption that we had a democratic system, and that created complacency among the people and the political parties. No one seemed interested in improving the system.

Now, we see that democracy is necessary. Finally, the progressives are talking about democracy. The revolutionary groups are talking about democracy. Young people are talking about democracy. People are talking about the needs for checks and balances, the need to develop a genuine multi-party system in which every voice is heard.

An Opportunity for Change

We have seen thousands of people protest on the streets demanding democracy. This is a good moment for civil society. The protesters – social movements like feminists, environmental groups, farming groups, workers – are coming together for the first time with a common aim. They are still consolidating, but there is the potential for them to form new political movements or support candidates from existing political parties.

There is renewed interest in our work running democracy training for people from across the political spectrum.

This is an opportunity, and it is important that the existing political parties recognize this too. The leaders of the two traditional parties are largely old and set in their ways. They think the problem is just Bukele. They are not looking at flaws in the democratic system that facilitated his rise to power, and there needs to be that moment of self-reflection.

The political parties need to change and recognize that their entrenched polarization and their inability to work together over ideological lines played a large part in fueling that disillusionment that allowed Bukele to seize the narrative.

“We needed this broken moment to think about democracy.”

What happened in El Salvador is also a warning to other countries not to take democracy for granted. It is a work in progress, and without sustained effort and investment, it can start to recede with alarming speed.

The young people in El Salvador today recognize this. We needed this broken moment to think about democracy. In the last months, finally I have a little hope, because the young people are talking about democracy, they are talking about dialogue. Now as Salvadorian democrats – with the support of the international community – we need to make sure we support those dreams of true democracy.

A version of this article appeared on the Dutch-language Latin American online news magazine, La Chispa.